New Tech: An Energy Generating Brick

17 January 2019

This article originally appeared on the Kings' College London website.

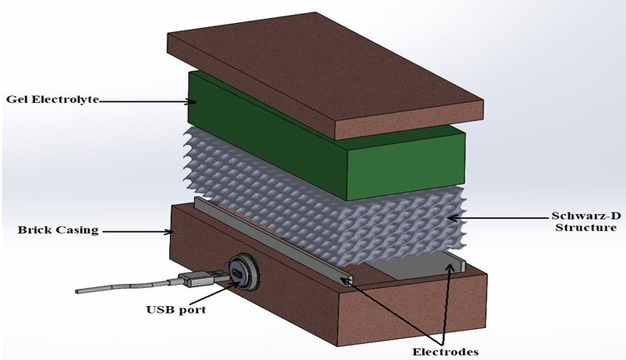

An international team of scientists, led by the King’s College Department of Chemistry in London has developed a thermogalvanic brick that generates electricity as long as the two faces of brick are at different temperatures.

The scientists revealed that this can take place through a balanced ‘electrochemical’ reduction and oxidation process occurring inside the brick at the two faces.

Essentially, as long as electrodes at these faces are at different temperatures, the electrochemical reactions are able to occur and electricity can be generated.

The scientists also stated that the compounds inside are not consumed, do not run out and can never be overcharged.

As long as there is a temperature difference there can be electricity. For example, if a house or shelter’s outside wall is sunny and hot, but the interior shaded and cool, electricity can be produced by the wall.

By using gelled water inside the brick and adding a 3D printed interior based upon a Schwarz D minimum surface structure, the thermogalvanic bricks were stronger than regular household bricks, in addition to holding improved insulation qualities.

The team - including scientists from Arizona State University and UNSW Sydney, as part of a PLuS Alliance partnership – believe that this could help provide access to affordable and sustainable energy, independent of an electrical grid.

Four undergraduate students, including two King’s Chemistry students, also helped implement the key experiments to prove these devices could work. The team has now filed a provisional patent for the bricks.

In announcing the news, Dr Leigh Aldous , Senior Lecturer in the Department of Chemistry explained that the idea is that these bricks could be 3D printed from recycled plastic and be used to quickly and easily make something like a refugee shelter.

"By the simple act of keeping the occupants warmer or cooler than their surroundings, electricity will be produced, enough to provide some nighttime lighting, and recharge a mobile phone," he commented.

"Crucially, they do not require maintenance, recharging or refilling. Unlike batteries, they store no energy themselves, which also removes the risk of fire and transport restrictions."

Conor Beale, a 2nd-year undergraduate Chemistry student at King’s who worked on the project also noted how we can take something so common and never thought about, such as temperature difference in houses, and use it to create electricity.

"For a family living in a developing country, this could have a substantial impact."